A lot has been written and signed about the work of Lydia Callis who interpreted for Mayor Bloomberg as New York City prepared for the arrival of Hurricane Sandy. Parodies showed up on YouTube and even Saturday Night Live – and the Deaf community and its allies pushed back against these attempts at humor that were directed at a language that the so-called humorists had no understanding of.

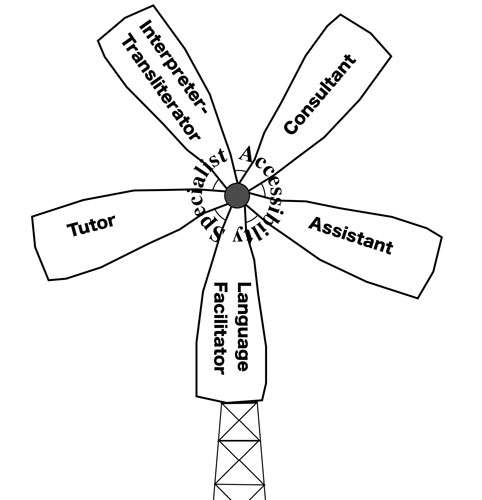

I want to share some thoughts on this topic that are more specific for interpreters in thinking about our work.? In doing it, I am indebted to a framework developed by Robert Lee and Peter Llewellyn-Jones that looks at the “role-space” of interpreters.? I saw their presentation on this topic at the 2012 CIT Conference and I found it to be an incredibly useful way of looking at our work.

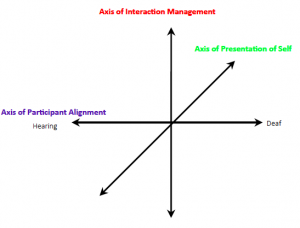

Here it is in nutshell that doesn’t do justice to it – but I hope will entice you to be interested in learning more. In analyzing the choices that interpreters make in interactions, they suggest that our work happens along three axes.

- Presentation of Self – How much or how little interpreters interject themselves into an interaction

- Participant Alignment- To what degree does the interpreter align with the deaf or the hearing participant

- Interaction Management – How much influence does the interpreter exert over the way that the participants interact

In all interactions, interpreters need to make choices about how to move along those different dimensions.

Enter the case of interpreting for a mayor who is providing information to a citizenry about what to do to stay safe in a hurricane.? What choices are faced by that interpreter?

First of all, part of the point of interpreting in emergency management situations is to get the information out to as wide an audience as possible.? So, the interpreter then gets to share the television screen with the mayor – in some ways getting equal billing.? (This means a higher level of presentation of self.)? For people unaware of Deaf culture or American Sign Language, they may be more used to seeing interpreters sequestered in a bubble – not integrated into the actual situation.? So, that high presentation of self may have been jarring for some people.

Second, the interpreter had to make a choice about alignment.? To the vast majority of people watching the clips, the obvious person to align with is the Mayor.? Yet she obviously wasn’t matching the affect of the mayor – who was speaking very calmly and would not be described as a dynamic speaker.? So, what was going on there?

While I don’t have any special insight into the choices of this particular interpreter, my guesses are that in the Emergency Management situation, the interpreter was making linguistic choices that did not align with how the mayor was presenting the information, but in the way that she thought would be most accessible to the deaf people who would be relying on getting the information via ASL.

So, her language choices were highly visual and direct which made them open to parody by the likes of Saturday Night Live.? But they also may have conveyed life-saving information to deaf people who would not have had access to it otherwise.

As I have talked with hearing people who have shared the parodies with me, I have used this framework to open up their eyes a little bit more to the work we do and the choices we make as interpreters.? In your conversations about your work with others, I hope these thoughts might be helpful for you as well.