Introductory Details

Goal:

- To provide a practical and theoretical framework for teaching ASL in Elementary Settings

Learning is in the Details….perhaps a strange title for a sign language approach, but it is one I firmly believe is true for elementary settings. In order to engage students in the learning process, I think it is vital that, as much as possible, all the activities be tailored to fit the specific situation in which you are teaching. That as much as possible, the details of the activity should be the details of your classroom. It is my hope that you will find this curriculum to be a tool that gives you the resources to do that in your own setting and assists you in creating more accessible class-rooms for Deaf and hard of hearing students. See the final lesson on “Creating Your Own Units”for more specifics about how to go about this process.

Purpose

Purpose of this Project

The impetus for this project came out of my experience working as an educational interpreter and seeing how important it was for

Deaf students to have peers who could sign. I say it over and over throughout the curriculum, but my great hope is that the resources contained here will contribute to helping make mainstream classes a more welcoming place for Deaf and Hard of Hearing students.

Before you go on, let me introduce myself on video and give you an ASL version of what this curriculum is all about.

The Philosophical and Theoretical Stuff

The Philosophical and Theoretical Stuff

This activity packet is designed to provide support for interpreters and others who are called on to teach sign language for classrooms that seek to include Deaf and hard of hearing students. The lessons contained were developed in my experience of working at Lakewood Elementary school in Duluth, Minnesota. I found these activities to be helpful in creating a classroom environment that allowed for more independent and direct communication—and the possibility for deaf students to feel a part of the community.

Who should teach ASL?

Who Should Teach American Sign Language?

I want to recognize that providing support to interpreters teaching sign language is not an idea without controversy. Deaf people, through organizations like the National Association of the Deaf and the American Sign Language Teachers’ Association (ASLTA) are pushing for higher standards for people who teach sign language, to ensure that the integrity of the language is maintained. Thus,there is grave concern about interpreters who may not be competent in the language passing on their own incompetencies. ASLTA’s website, http://www.aslta.org, is a good resource for exploring some of these perspectives and concerns. ASLTA asserts clearly that teachers of ASL need to be competent both in the language and in methods of teaching. They suggest that teachers should have been using ASL on a regular basis for at least 5 years and be involved in ongoing continuing education to further their skills and knowledge in both ASL as a language and in how to teach it. These concerns of the Deaf community about maintaining the integrity of ASL through higher standards for teachers are extremely important for anyone considering teaching sign language to reflect upon. Interpreters who take on this task need to be very cognizant about their role not only in teaching that classroom, but in recognizing the special role that American Sign Language plays in the life of the American Deaf community. I firmly believe that maintaining the integrity of the language is a responsibility that should not be taken lightly.

Yet, young deaf children desperately need to have peers with whom they can communicate directly. What is abundantly clear in the experiments with mainstreaming and inclusion is that the presence of an interpreter, even a qualified one, is no assurance that Deaf students’ experiences will be successful. Deaf and hard of hearing children need to have access to communication through a multitude of sources—and it is important that it isn’t all channeled through an interpreter.

The fact that Deaf students need to have signing peers does not necessarily mean that interpreters need to be the ones doing the teaching. Other options may exist in some situations, including bringing in a member of the Deaf community to teach on a weekly basis, or using Teachers of D/HH students who have experience both with sign language and with teaching. In some situations, these options may be workable, but often they aren’t even really options.

What I think is important to consider in discussions about who should teach sign language to young children is understanding how critical it is for students to have a relationship of trust with their instructor. As children grow, they are able to learn more effectively from people with whom they have little history or context, but for young students, it is absolutely imperative that student see this person often, build trust, and be able to create a relationship that fosters linguistic development.

Regardless of who teaches, balancing the concerns for individual students and larger concerns of Deaf people needs to be something that happens within the context of conversation with and respect for the Deaf community.

A Deaf Perspective

Debbie Peterson, a colleague of mine who has a great deal of experience teaching ASL and interpreters, shares her perspective on having interpreters teach ASL in elementary classrooms. She raises many important concerns that need to be taken very seriously in implementing a curriculum such as this one.

An Integrated Approach

An Integrated Approach

This project grew out of my experience of the “Signing Naturally” curriculum and its functional-notional approach. This method of teaching language grows out of “Speech Act” theory, that is the theory of discourse that the principal reason for language is to do something, to get something.(One of the characters in a play entitled the “The Meaning of Life, the Universe, and Everything,” declares: “I believe that people developed language out of a deep inner need to complain.” ) Our need to complain, our need to have the ketchup passed to us, our need to learn about each other—it is out of these needs that language arose. And so, “Signing Naturally” developed a curriculum that places students in situations that practices these different functions of language.In my own experience, I found that young children were not able to resonate with the situations of a curriculum developed for adults, but they were extremely receptive to the functional-notional approach.

So, in developing new activities within the context where I was working, I drew on the experiences of the particular classroom and created dialogues and activities based on what students were actually needing to communicate about during their day.While I hope that the activities that I have recorded will prove helpful, my real hope is that they will provide enough practice with the process that you will be able to create individual dialogues and group activities for any topic. So, that when the lessons run out in the curriculum, you will always be able to create new lessons that are integrated into the life of your specific classroom.

Teaching Language, Not Just Signs

Teaching Language, Not Just Signs

As part of a workshop I gave in Wisconsin on Ethics and Role of Educational Interpreters, one interpreter explained that in teaching sign to the classroom in which she worked, she tried to be very clear that she only taught signs, not language. That is, that she was only comfortable teaching vocabulary, but not the broader aspects of language that these vocabulary items are embedded in. Her comments have stayed with me, and I think they represent an honest perspective and also a commentary on the state of materials targeted for teaching sign language in elementary settings. Most of the resources available only teach individual signs, but not the whole of language. Sadly, this misses out on the potential of young children for learning language. More and more, language immersion programs are being instituted in elementary schools to capitalize on the fact that young brains are wired for learning language.

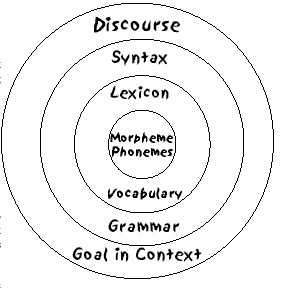

For ASL instruction to be successful in teaching language, interpreters and teachers need to be cognizant of the different linguistic levels that exist. The following is a brief summary of these strata of language–and is intended to more raise questions that push you on to further understanding of the linguistic structure of discourse. In this overview, I move from the more specific, smaller units to the broader and larger units of language.

For ASL instruction to be successful in teaching language, interpreters and teachers need to be cognizant of the different linguistic levels that exist. The following is a brief summary of these strata of language–and is intended to more raise questions that push you on to further understanding of the linguistic structure of discourse. In this overview, I move from the more specific, smaller units to the broader and larger units of language.

Phonological and Morphological Level

Linguists actually separate this level into two separate parts, but for the purpose of this overview, they can serve as those units that are the components parts of a single sign. Often called the parameters of a sign, they include:

- handshape,

- movement,

- location,

- palm orientation, and

- non-manual markers.

In teaching language, an instructor needs to be aware of whether or not a student is producing a sign correctly by assessing these parameters. However, it is important to expect that students will mispronounce signs and to focus on continually exposing children to the correct way of creating signs, rather than attempting to correct individual errors.

Lexical Level

This is the level of teaching vocabulary and the one which most materials are geared to, and to which adult learners cling to. It’s symbolized most clearly by the question of “What’s the sign for…?” It is at this level that there is great regional variation in language, and teachers of ASL need to prepare students to understand that different people may have different signs for the same concept.

Syntactic Level

This is the level of grammar and syntax. For teachers of ASL, it is important to be familiar with the variety of basic sentence types:

- declaratives,

- negatives,

- imperatives/commands,

- rhetorical question,

- WH-questions,

- Yes/No questions,

- conditionals, and

- topic- comment structures.

ASL, like other languages, has flexibility in its syntactic structure and instructors need to expose their students to a variety of grammatical structures.

Discourse Level

This is the level that holds together all of the other levels of language, and allows us to use language to accomplish certain functions. In doing analysis of discourse, linguists look at the parts of a text or interaction: openings; closings; transitions; cohesion; utterance boundaries; prosody; the list goes on. Discourse also looks at the functions that language carries out: exchanging information, expressing opinions; asking for information/assistance; complaining; explaining procedures; giving directions; telling stories; etc. So, in teaching ASL, instructors need to expose students to how these language features and functions are expressed in sign.

In my opinion as someone who is not a native signer, I think non-native teachers need to be especially aware of the way that linguistic space functions to hold together ASL discourse. The reality that all signing happens in a visual and spatial format is crucial-

-and for native English speakers–a challenge to begin to understand and appreciate.

The units contained in this curriculum are designed to allow the opportunity to go beyond merely teaching signs, and to teach broader levels of language. Through introducing vocabulary, having both individual and group dialogues, and using stories, students can gain exposure to both the smaller linguistic structures and the broader aspects of grammar and discourse.

The Structure of Units

The Structure of Units

When working in an elementary school, one can’t help but notice patterns within the daily routine—and yet how children can see the same activity as something new if one element is changed.

During kindergarten gym class, we played the same game of tag where some people are in the middle and it—and others try to run across the gym without getting tagged. Over and over, the kids played this game, but it was always new to them because it was given different words to go with it. Sometimes, those who were “it” were police, and the runners were cars. Other times, it was sharks and fish. The list of characters went on and one, but it was essentially the same game.

This reinforced for me how much kids enjoy familiar structures, and can build on these to incorporate new words and new ideas.

The Units I have outlined follow very repetitive structure. Generally, they start out with an introduction of vocabulary, then a

individual dialogue where students come up to the front, and with your guidance, go through a specific dialogue. Then, based on this individual work, do some kind of group activity which forces all to participate and try out the language. This pattern allows for students to first get exposure to the language; then choose to participate, but still have the option of only watching their peers do it; and finally all of them to take part in a group activity that doesn’t have the pressure of everyone watching them.

At the end of each Unit is an example of a story that can be used to provide some closure and further exposure to those language structures addressed in the unit. A Unit at the end of the curriculum goes into more depth about this structure, and how to create your own units.

Introduction of Vocabulary

Introduction of Vocabulary

The important part of introducing vocabulary items is that they are always given in the context of a larger language segment. All of the pictures or lists used for introducing vocabulary can be clicked on to see an example of how to introduce an item, show it used in a sentence, and then repeated as an individual sign. For the sentence, don’t worry about students understanding the complete sentence. What is important is that they see it introduced as part of a language in use.

Here’s an example of introducing the vocabulary item for “Name”:

Individual Dialogue Process

Individual Dialogue Process

Individual dialogues provide opportunity for students to receive guided practice in trying new language skills, and to let others still get exposure to the language without having yet to put it into practice. What I have found to be most useful is to ritualize the process, so that students don’t have to think about what the steps are, but can focus more easily on the language usage itself.

Here’s what I found to be successful.

First demonstrate the dialogue, playing both parts. (This also provides some initial exposure to the process of role shifting and depiction.) I find it helpful to do it a couple of ways, often providing different answers to the question, so students can see different results. You can click on the video below to see an example.

Then, pull in a dependable student to play one of the roles. I generally liked to work with the Deaf or Hard of Hearing student in this role because it is a part of a process of nurturing the possibility that they could see themselves in the role of teacher.

For rotating through a dialogue, I always begin and then pick a competent student (often the Deaf student) to be the first volunteer. I play the part of the questioner, and then after that, the first student plays that part and I choose the next volunteer. After the next round, the first student then gets to select the next volunteer and the second student becomes the questioner. Allowing students to choose the next volunteer is crucial to engaging them in wanting to come up and try the dialogue because they experience a great feeling of power as they look out at their classmates and get to choose who comes up next. This rotation style needs monitoring, however, because oftentimes, students choose the same people over and over. So, at times, I need to intervene and say that only people who didn’t get a turn last time can raise their hands. Or sometimes, I say that boys need to pick a girl and vice versa. Doing this allows you to maintain a familiar pattern, but also ensures that everybody who wants to participate can.

Group Activities

Group Activities

I always start my group activity directions both signing and voicing, with the sentences: “I’m going to give you directions and then I will count to ten. When I get to ten, you will….(and give directions and then start counting to ten.)” I find that the use of voice is necessary to make sure students have enough understanding to be able to engage in the activity. But I would encourage you to experiment with using as little voicing as possible. Also note that I use counting here to mark the beginning. As students become more proficient with counting, I change the number we count up to…moving from 10 to 15 and beyond. See an example below.

Stories—Narrative Techniques

Stories—Narrative Techniques

Each Unit ends with a story. There is a movie to give an example of what the story could be. Most important is to customize the story to fit both what you taught within that unit, and who the students are within your classroom. I cannot stress enough the importance of telling a story that has these students as characters. It is this detail that engages students in wanting to understand the story, in wanting to pay attention.

It’s also important to try to include ASL narrative features. Some examples that are prevalent are use of spatial mapping and depiction which includes classifier predicates, role shifting, and shifting between reference scales. This last feature is what Bernard Bragg described as “Visual Vernacular” and what others have called “Close-Up” and “Far shot.” Shifting back and forth between these reference scales is an important means of creating texture within a story and making it more visually engaging.

It is also helpful to consider genres of stories that are intended to build literacy. In another project, Goats, Trolls & Numbskulls, Lise Lunge-Larsen shares about the cumulative genre of folktales and how they are designed with young children. The video below shares Lise’s explanation of this genre and gives an example. In many of the stories for the Units, I use the cumulative approach to build a story with readily identifiable patterns that continue to introduce new concepts and vocabulary – but within an established framework.

Checking for Comprehension

Checking for Comprehension

After telling a story, I generally ask a series of questions to check for comprehension—or to assist in the comprehension of those who didn’t get it the first time around. In doing so, I use both voice and sign—and interpret any answers that students give in voice.

Here are some questions I might ask for this sample story of Daniel’s.

- Where did the story take place?

- Who was the first person there?

- What was Daniel doing?

- Who raced with Daniel?

- Who won the race?

As students develop competency, you can shift from using your voice and expecting them to respond with their voice, to using sign only.

Breath of Fresh Air Activities

Breath of Fresh Air Activities

The final unit with activities includes focus on colors, shapes, numbers, and spelling. These activities can be repeated over and over-

– adapted to fit the material in the unit you are working on or the level that students are at. If the routine of going from Individual

Activity to Group Activity needs to have some variety, I suggest looking through this unit to see if there is something that can provide a breath of fresh air to your lessons.

Graphic Art Options and Engaging Students

Graphic Art Options and Engaging Students

Within the appendices, I have provided of pictures in different mediums. Some are from clip art, some are digital pictures, and some are drawings of my own creation. Given this lack of consistency, I want to provide a little reflection on what constitutes effective pictures for teaching young children. There is no question in my mind that pictures are needed for introducing vocabulary items for lessons.

In adult curricula, drawings are generally line art that are easily reproducible via copy machine. Some of what I have created in the appendixes are designed for reproduction, but much of it is in color—and designed to be able to be printed off as one copy

for demonstration.

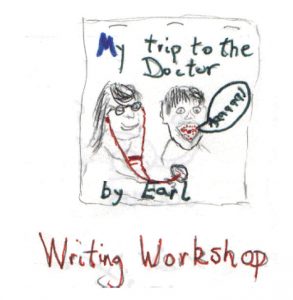

But I have also included some scans of some my own original drawings that I used for teaching in the classroom. I include them

not because I want to give evidence of my lack of formal training in art, but to show that what creating original drawings may lack in

artistic quality, it allows for adding the particularity of a situation that can engage students.

Let me elaborate on a couple of examples. All of you can see that the picture to the left is of a man signing “Tree” with a drawing of a tree. However, in the classrooms where I was working, all of the students saw a picture, not of a man, but of “Doug.” The fact that it was a drawing of me engaged the students in the learning. Furthermore, the fact that they saw me creating these pictures stirred their interest in what lessons lay ahead. So, I encourage you to use the ideas that I give here, but to create your own pictures that will fit your particular setting. Whether by crayon or camera, having pictures that are specific greatly serve to engage young students in the learning process.

Let me elaborate on a couple of examples. All of you can see that the picture to the left is of a man signing “Tree” with a drawing of a tree. However, in the classrooms where I was working, all of the students saw a picture, not of a man, but of “Doug.” The fact that it was a drawing of me engaged the students in the learning. Furthermore, the fact that they saw me creating these pictures stirred their interest in what lessons lay ahead. So, I encourage you to use the ideas that I give here, but to create your own pictures that will fit your particular setting. Whether by crayon or camera, having pictures that are specific greatly serve to engage young students in the learning process.

As well, this picture of “Writing Workshop,” used in Unit 7, is based on the work of  one particular student in a second grade. All his stories, at some point or another, had one character shouting, “Aaaaaaaa!!” So, in my representation of this activity, I included that detail of a character saying this—which had tremendous meaning for that specific class.

one particular student in a second grade. All his stories, at some point or another, had one character shouting, “Aaaaaaaa!!” So, in my representation of this activity, I included that detail of a character saying this—which had tremendous meaning for that specific class.

Because I included these types of details, students were always looking to see if they could recognize themselves or their classmates in the pictures and activities. And that is the reason for selecting the title, “Learning in the Details.” It is this attention to detail that assists in engaging students in the language learning process.

Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students as Assistant Teacher

Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students as Assistant Teacher

One goal of this is teaching sign language to hearing peers of Deaf students. But another important objective is to mentor deaf and

hard of hearing students in their ability to be teachers of the language. For these students, it begins to open up the possibility of

teaching ASL as a career—or more broadly the possibility that they could become teachers or other kinds of professionals. Furthermore, it can emphasize the skills of students who often struggle in other parts of the school day, and thus can be a support

to a student’s sense of worth in a classroom.

I have also worked with Hard of Hearing students who were resistant to the notion of needing either sign language or an interpreter. So, while an IEP team had decided that an interpreter was a necessary support for their educational experience, the student themselves didn’t necessary believe it or didn’t want to be singled out for being different. However, through being able to be an assistant teacher, the hard of hearing student realized the importance and value of knowing sign in terms of teaching his or her peers—and seeing the enthusiasm that other students had for learning ASL. In this way, the hard of hearing students were indirectly influenced to both learn some more sign language and accept that sign language could be of value.

As an extension of this philosophy, I invited Daniel Durant, Jennifer Langdon-Larson, and Ketsi Carlson to join me in serving as language models for the activities. In addition, Debbie Peterson provided some modeling.

On Grammar and Digital Video

On Grammar and Digital Video

In my dialogues, I do not attempt to use a transcription system to show ASL in a written form. In part, this is in recognition that this curriculum is not designed so much to teach certain forms of ASL as it is to teach peers of deaf students to sign in a way that they can communicate. Which means, that for certain deaf students, it may be more effective to teach a similar mode of communication as used by the student – rather than trying to teach some textbook form of ASL. However, teaching more textbook ASL may also be a way to help the deaf student gain a more standard use of sign. Interpreters and teachers using this resource will have to assess what are the specifics of their situation and teach with those parameters in mind.

I have also attempted to use digital video in reducing the need for the use of written transcription. I have included links to movies as often as possible to demonstrate potential ways to sign a question that is written in English, or ways to demonstrate vocabulary items.

The movies in no way represent the only way to interpret that question, but they do provide some guidance for sentence structure that you might want to use. Throughout this curriculum, there are almost 200 movie links. So, if you’re looking for an idea of how to

sign something, look on the page for a sample video.

Relating with the Classroom Teacher

Relating with the Classroom Teacher

In order to utilize these activities, you need to develop a good working relationship with the classroom teacher. It’s important for the teacher to see how your work will benefit all of the students in the classroom, and how it can reinforce lessons that are taught in other subject areas. Once teachers understand this, it is much easier to negotiate for an amount of time to teach these lessons. I find that short amounts of time on a frequent basis are much more successful.

These lessons are designed to be taught in 15-20 minute segments. I would recommend building into a class schedule at

least 3 sign language lessons per week. Additionally, it is important to figure out with the classroom teacher how to handle classroom management during the course of sign language lessons. Because an interpreter who teaches sign language plays a different role during that time, it is important to be clear with both the teacher and the students who will be responsible for disciplining students who do not behave appropriately during sign language time. I have found that it is possible for classroom

teachers to maintain this responsibility or for interpreters to take it over during this time, but then be very clear that when sign

language time is over, the interpreter no longer is responsible for classroom management. Whatever decision is made, I think it is

important that teacher and interpreter make it together and that changing roles are communicated clearly to the students.

Acknowledgements/Meet the Language Models

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Daniel Durant, Jennifer Langdon-Larson, Ketsi Carlson, and Debbie Peterson for agreeing to serve as language models for many of the sample movies. Their gifts with language and willingness to share benefitted this project greatly. As well, I

thank the teachers of Lakewood Elementary School in Duluth, Minnesota, who afforded me the freedom to turn my ideas into effective ways of creating more accessible classrooms.

Meet the Language Models

For Other Sign Language and Interpreting Resources

For Other Sign Language and Interpreting Resources

Please check out more of this website to see other resources which have been developed to support interpreters in their work to provide higher quality services.

Here are some other resources related to teaching ASL.

- ASL University: American Sign Language University is resource site for ASL students and teachers. Here you will find information and resources to help you learn ASL and improve your signing.

- Signing Savvy: Signing Savvy is a sign language dictionary containing several thousand high resolution videos of American Sign Language (ASL) signs, fingerspelled words, and other common signs used within the United States and Canada.

- ASL Teacher’s Association (ASLTA): ASLTA is a national professional organization of American Sign Language and Deaf studies teachers.

Doug Bowen-Bailey

October 2002

Updated November 2016

Credits

This project is a creation of

Originally created in 2002.

Updated and moved online in 2016.